Optiscope is an experimental Lévy-optimal implementation of the pure lambda calculus enriched with native function calls, if-then-else expressions, & a fixed-point operator.

Being the first public implementation of Lambdascope 1 written in portable C99, it is also the first interaction net reducer capable of calling user-provided functions at native speed. This combination allows one to (1) embed all primitive types & operations through C FFI, (2) interleave lazy evaluation with direct side effects, and (3) let optimal reduction share calls to pure C functions just like ordinary β-reductions. As such, Optiscope can be understood as an optimal λ-calculus reducer extended to sharing foreign computation.

In what follows, we briefly explaine what it means for reduction to be Lévy-optimal, & then describe our results.

$ git clone https://github.com/etiamz/optiscope.git

$ cd optiscope

$ ./command/test.sh

Optiscope offers a lightweight C API for writing programs in the extended lambda calculus; these programs are automatically translated to interaction nets under the hood. To see Optiscope in action, consider the example program examples/lamping-example.c, which evaluates to the identity lambda under weak reduction to interface normal form 2:

#include "../optiscope.h"

static struct lambda_term *

lamping_example(void) {

struct lambda_term *g, *x, *h, *f, *z, *w, *y;

return apply(

lambda(g, apply(var(g), apply(var(g), lambda(x, var(x))))),

lambda(

h,

apply(

lambda(f, apply(var(f), apply(var(f), lambda(z, var(z))))),

lambda(w, apply(var(h), apply(var(w), lambda(y, var(y))))))));

}

int

main(void) {

optiscope_open_pools();

optiscope_algorithm(NULL, lamping_example());

optiscope_close_pools();

}This is the exact Optiscope encoding of the example discussed by Lamping in 3.

By adding the following lines into optiscope.h:

#define OPTISCOPE_ENABLE_TRACING

#define OPTISCOPE_ENABLE_STEP_BY_STEP

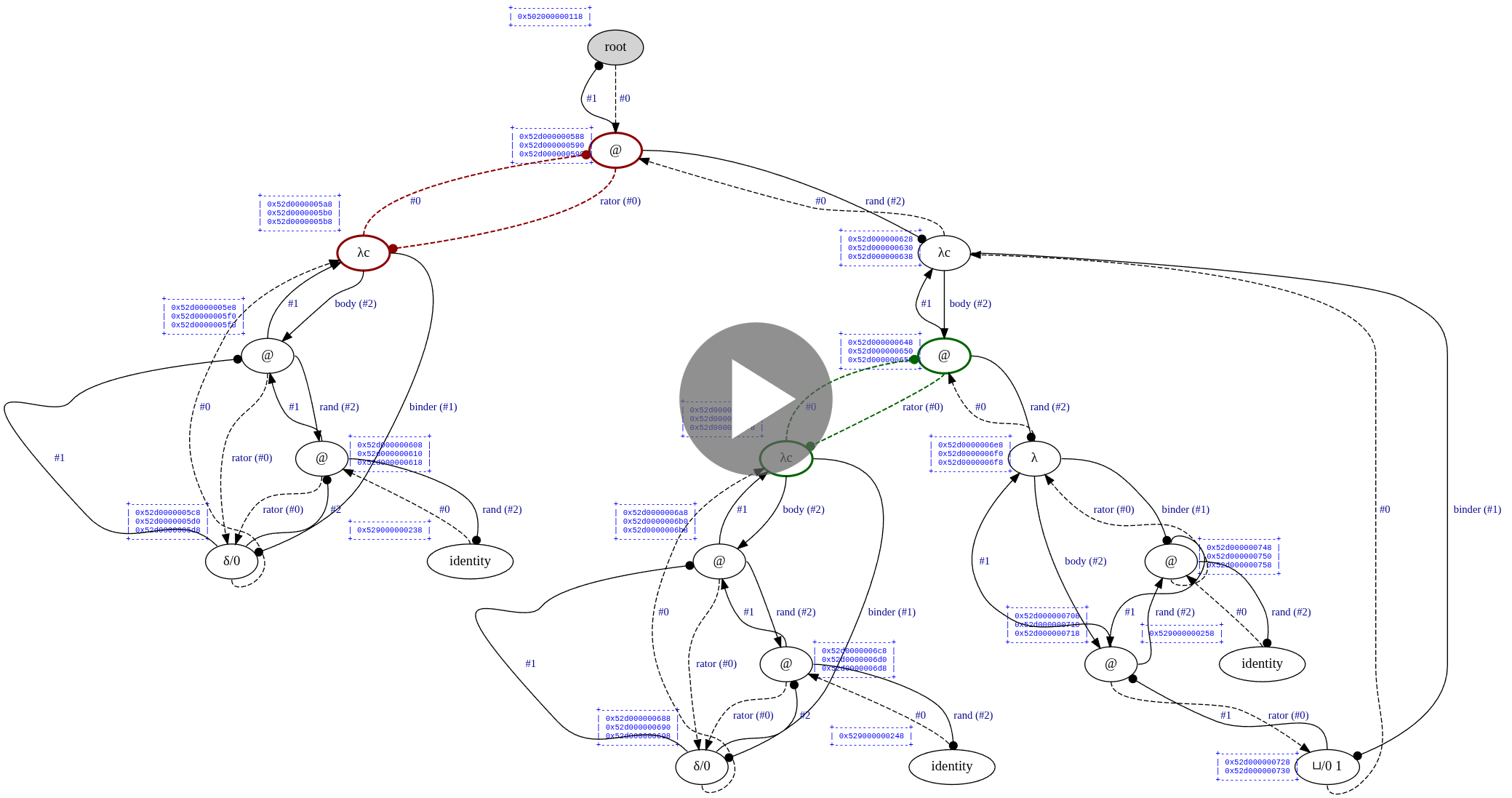

#define OPTISCOPE_ENABLE_GRAPHVIZ& typing ./command.example.sh lamping-example in your shell, Optiscope will visualize each interaction step in target/state.dot.svg before you presse ENTER to fire the red interaction:

We mimicke full reduction in terms of weak reduction applied to a metacircular interpreter for pure lambda calculus terms. Consider another example examples/2-power-2.c, which computes 2^2 using Church numerals:

#include "../optiscope.h"

static struct lambda_term *

church_two(void) {

struct lambda_term *f, *x;

return lambda(f, lambda(x, apply(var(f), apply(var(f), var(x)))));

}

static struct lambda_term *

church_two_two(void) {

return apply(church_two(), church_two());

}

int

main(void) {

optiscope_open_pools();

optiscope_algorithm(stdout, church_two_two());

puts("");

optiscope_close_pools();

}By passing a file stream to optiscope_algorithm, in this case stdout, we can see the resulting normal form:

$ ./command/example.sh 2-power-2

(λ (λ (1 (1 (1 (1 0))))))

Of course, such an implementation of full reduction is very inefficient -- we use it onely for testing purposes. (Implementing full reduction natively would require a more complex machinery, namely global graph traversing; also, Lévy-optimality requires following a specific order of reduction, but the leftmost-outermost order would enter a cycle when following backpointers.)

See the example examples/palindrome.c with a detailed step-by-step explanation in comments.

In this section, we give well-formednesse rules for side-effectfull computations in Optiscope.

We take our inspiration from the use of monads in call-by-need functional programming languages, such as Haskell. The intuition is as follows: whenever we would write _ <- action; k in Haskell, we write perform(action, k) in Optiscope; whenever we would write x <- comp; k in Haskell, we write bind(x, action, k) in Optiscope; whenever we would end execution with action in Haskell (e.g., putStrLn "goodbye" at the end of do-notation), we doe the same in Optiscope.

We write comp/pure for pure computations, i.e., those not conteyning bind or perform, & comp/impure for computations involving side effects. The formal rules for impure computations are as follows:

- If

fis a side-effectfull function, thenunary_call(f, token)/impure, wheretokenis a cell passed downwards. - If

fis a side-effectfull function &rand/impure, thenbinary_call(f, rand, token)/impure, wheretokenis a cell passed downwards. - If

action/impure&k/impure, thenperform(action, k)/impure. - If

action/impure&k/impure, thenbind(x, action, k)/impure. - If

action/impure&if_then/impure&if_else/impure, thenif_then_else(action, if_then, if_else)/impure. - If

comp/pure, thencomp/impure.

The onely difference between Optiscope and Haskell-style monads is that, while monads are first-class citizens in Haskell, they merely manifest themselves as well-formednesse rules in Optiscope. While the Haskell approach allows for more flexibility & preserves the conceptual purity of I/O functions, it requires the I/O monad to be incarnated into the language & to be treated specially by the runtime system; on the other hand, the Optiscope approach onely requires carefull positioning of effectfull computation, which can be easily achieved through a superimposed type system that implements the rules above.

Optimal XOR efficient? I made a fairly non-trivial effort at optimizing the implementation, including leveraging compiler- & platform-specific functionality, yet, our benchmarks revealed that optimal reduction à la Lambdascope performes many times worse than unoptimized Haskell & unoptimized OCaml; for instance, whereas Optiscope needs approximately 2 minutes to execute an insertion sort on a Scott-encoded list of 10'000 elements (in decreasing order), the Haskell implementation handles the same amount of elements in just 2 seconds! (Optiscope's abstract algorithm needs approximately 50 seconds, which is still very slow compared to Haskell.)

Similar stories can be told about the other benchmarks. At one moment, I wondered if I merely implemented Lambdascope incorrectly because of this excerpt from the paper:

A prototype implementation, which we have dubbed _lambdascope_, shows that

out-of-the-box, our calculus performs as well as the _optimized_ version of the

reference optimal higher-order machine BOHM (see [2]) (hence outperforms the

standard implementations of functional programming languages on the same

examples as BOHM does).

This is a very interesting excerpt, because while it is concerned with efficiency, it says nothing in particular about it, save that their implementation is as fast as BOHM. So the question is: how fast is BOHM?

I downloaded BOHM1.1 & wrote the following Scott insertion sort benchmark for 1000 elements:

Show

def scottNil = \f.\g.g;;

def scottCons = \a.\b.\f.\g.(f a b);;

def scottSingleton = \x.(scottCons x scottNil);;

def lessEqual = \x.\y.if x <= y then 1 else 0;;

def scottInsert = rec scottInsert = \elem.\list.

let onNil = (scottSingleton elem) in

let onCons = \h.\t.

if (lessEqual elem h) == 1

then (scottCons elem (scottCons h t))

else (scottCons h (scottInsert elem t)) in

(list onCons onNil);;

def scottInsertionSort = rec scottInsertionSort = \list.

let onNil = scottNil in

let onCons = \h.\t.(scottInsert h (scottInsertionSort t)) in

(list onCons onNil);;

def scottSumList = rec scottSumList = \list.

let onNil = 0 in

let onCons = \h.\t.h + (scottSumList t) in

(list onCons onNil);;

def generateList = \n.

let go = rec go = \i.\acc.

if i < n

then (go (i + 1) (scottCons i acc))

else acc in

(go 0 scottNil);;

def benchmarkTerm =

(scottSumList (scottInsertionSort (generateList 100)));;

benchmarkTerm;;

Then I typed #load "scott-insertion-sort.bohm";; and... it hanged my computer.

For a couple of hundred elements, it executed almost instantly, but it was still of no rival to Haskell & OCaml.

Also read the following excerpt from 4, section 12.4:

BOHM works perfectly well for pure λ-calculus: much better, in average, than all

"traditional" implementations. For instance, in many typical situations we have

a polynomial cost of reduction against an exponential one.

Interesting. What are these "typical situations"? In section 9.5, the authors provide detailed results for a few benchmarks: Church-numeral factorial, Church-numeral Fibonacci sequence, & finally two Church-numeral terms λn.(n 2 I I) & λn.(n 2 2 I I). On the two latter ones, Caml Light & Haskell exploded on larger values of n, while BOHM was able to handle them.

Next:

Unfortunately, this is not true for "real world" functional programs. In this

case, BOHM's performance is about one order of magnitude worse than typical

call-by-value implementations (such as SML or Caml-light) and even slightly (but

not dramatically) worse than lazy implementations such as Haskell.

Looking at my benchmarks, I cannot call it "slightly worse", but rather "dramatically worse". The authors doe not elaborate what real-world programs they tested BOHM on, except for a quicksort algorithm from section 12.3.2 & the append function from section 12.4.1, for which they doe not provide comparison benchmarks with traditional implementations.

Finally, the authors conclude:

The main reason of this fact should be clear: we hardly use truly higher-order

_functionals_ in functional programming. Higher-order types are just used to

ensure a certain degree of parametricity and polymorphism in the programs, but

we never really consider functions as _data_, that is, as the real object of the

computation -- this makes a crucial difference with the pure λ-calculus, where

all data are eventually represented as functions.

Well, in our benchmarks, we represent all data besides primitive integers as functions. Nonethelesse, BOHM was still much slower than Haskell & OCaml with optimizations turned off.

What conclusions should we draw from this? Have Haskell & OCaml so advanced in efficiency over the decades? Or does BOHM demonstrate superior performance on Churh numerals onely? Should we invest our time in making optimality efficient, or goe for more traditional approaches? I have no definite answer to these questions, but the fact is: the practice of optimal reduction is still well behind industrial-strength runtimes; while it is true that Optiscope is a heavily optimized implementation of optimal reduction, this fact does not entail that it is very efficient compared to other approaches. For now, if you want to develop a high-performance call-by-need functional machine, it is presumably better to take the well-known Spinelesse Taglesse G-machine 5 as a starting point.

-

Node layout. We interpret each graph node as an array

aofuint64_tvalues. At positiona[-1], we store the node symbol; ata[0], we store the principal port; at positions froma[1]toa[3](inclusively), we store the auxiliary ports; at positions starting froma[4], we store additional data elements, such as function pointers or computed cell values. The number of auxiliary ports & additional data elements determines the total size of the array: for erasers, the size in bytes is2 * sizeof(uint64_t), as they need one position for the symbol & another one for the principal port; for applicators & lambdas having two auxiliary ports, the size is3 * sizeof(uint64_t); for unary function calls, the size is4 * sizeof(uint64_t), as they have one symbol, two auxiliary ports, & one function pointer. Similar calculation can be done for all the other node types. -

Symbol layout. The difficulty of representing node symbols is that they may or may not have indices. Therefore, we employ the following scheme:

0is the root symbol,1is an applicator,2is a lambda,3is an eraser,4is a cell, & so on until value63, inclusively; now the next9223372036854775776values are occupied by duplicators, & the same number of values is then occupied by delimiters. Together, all symbols occupy the full range ofuint64_t. The indices of duplicator & delimiter symbols can be determined by proper subtraction, but in most cases, they can be compared without any preprocessing. -

Port layout. Modern x86-64 CPUs utilize the 48-bit addresse space, leaving 16 highermost bits unused (i.e., sign-extended). We therefore utilize the highermost 2 bits for the port offset (relative to the principal port), & then 4 bits for the node phase, which can be

PHASE_REDUCTION,PHASE_GC,PHASE_GC_AUX, orPHASE_IN_STACK. The following bits constitute a (sign-extended) addresse of the port to which the current port is connected. This layout is particularly space- & time-efficient: given any port addresse, we can retrieve the principal port & from there goe to any neighbouring node in constant time; by storing information in phases, we avoid the need for any additional data structures. The onely drawback of this approach is that ports need to be repeatedly encoded & decoded; this pollutes the source code, but the computational cost of these operations is very neglegible. -

O(1) memory management. We have implemented a custom pool allocator that has constant-time asymptotics for allocation & deallocation. For each node size, we have a separate global pool instance to avoid memory fragmentation. On Linux, these pools allocate 2MB huge pages that lessen frequent TLB misses, to account for cases when many nodes are to be manipulated; if either huge pages are not supported or Optiscope is running on a non-Linux system, we default to

malloc.

- Weak reduction. In real situations, the result of pure lazy computation is expected to be either a constant value or a top-level constructor. Even when one seeks reduction under binders & other constructors, one usually also wants controlling definition unfoldings or reusing already performed unfoldings 6 to keep resulting terms manageable. We therefore adopt BOHM-style weak reduction 7 as the onely phase of our algorithm. Weak reduction repeatedly reduces the leftmost outermost interaction until a constructor node (i.e., either a lambda abstraction or cell value) is connected to the root, reaching an interface normal form. This phase directly implements Lévy-optimal reduction by performing onely needed work, i.e., avoiding to work on an interaction whose result will be discarded later.

(A shocking side note: per section "5.6 Optimal derivations" of 4, a truely optimal machine must necessarily be sequential, because otherwise, the machine risks at working on unneeded interactions!)

-

Garbage collection. Specific types of interactions may cause whole subgraphs to be fully or partially disconnected from the root, such as when a lambda application rejects its operand or when an if-then-else node selects the correct branch, rejecting the other one. In order to battle memory leaks during weak reduction, we implement eraser-passing garbage collection described as follows. When our algorithm determines that the most recent interaction has rejected one of its connections, our garbage collector commences incremental propagation of erasers by connecting a newly spawned eraser to the rejected port; iteratively, garbage collection at a specific port results in either freeing the node in question & continuing the propagation to its immediate neighbours or marking this node so that when it interacts, it will continue the garbage collection procedure appropriately. (However, we doe also eliminate some uselesse duplicator-eraser combinations as discussed in the paper, which has a slightly different semantics.)

Our rules are inspired by Lamping's algorithm 3 / BOHM 7: although perfectly local, constant-time graph operations, they doe not count as interaction rules, since garbage collection can easily happen at any port, including non-principal ones. -

Special lambdas. We divide lambda abstractions into four distinct categories: (1)

SYMBOL_GC_LAMBDA, lambdas with no parameter usage, called garbage-collecting lambdas; (2)SYMBOL_LAMBDA, lambdas with at least one parameter usage, called relevant lambdas; (3)SYMBOL_LAMBDA_C, relevant lambdas without free variables; & finally (4)SYMBOL_IDENTITY_LAMBDA, identity lambdas. Although onely one category is sufficient to expresse all of computation, we employ this distinction for optimization purposes: if we know the lambda category at run-time, we can implement the reduction more efficiently. For instance, instantiating an identity lambda boils down to simply connecting the argument to the root port, without spawning more delimiters; likewise, commutation of a delimiter node withSYMBOL_LAMBDA_Cboils down to simply removing the delimiter, as suggested in section 8.1 of the paper. -

Delimiter compression. When the machine detects a sequence of chained delimiters of the same index, it compresses the sequence into a single delimiter node endowed with the number of compressed nodes; afterwards, this new node behaves just as the whole sequence of delimiters would, thereby requiring significantly lesse interactions. The machine performes this operation both statically & dynamically: statically during the translation of the input lambda term, dynamically during delimiter commutations. In the latter case, i.e., when the current delimiter commutes with another node of arbitrary type, the machine performes the commutaion & checks whether the commuted delimiter(s) can be merged with adjacent delimiters, if any. With this optimization, the oracle becomes dozens of times faster on some benchmarks & uncomparably faster on others (e.g.,

benchmarks/scott-quicksort.c).- C.f. run-length encoding.

-

Delimiter scheduling. It is now natural to prioritize delimiter compression, so that more delimiters get compressed. One way to approach this is to "freeze" certain interactions of delimiters with other agents: roughly, instead of repeatedly propagating uncompressed delimiters to the root, we can first compresse as many delimiters as we can, & onely then propagate this single compressed delimiter to the root. For this kind of scheduling, we employ so-called barriers, which appear dynamically whenever a delimiter meets an operator agent or a duplicator. In the graph, this situation is depicted as "🚧 n", where n stands for the number of collected zero-indexed delimiters. Initially, n is initialized to the corresponding field of the delimiter facing the operator/duplicator agent, but when the barrier meets another zero-indexed delimiter, n is updated & the delimiter is removed from the graph. Contrariwise, when the barrier meets an agent which is not a zero-indexed delimiter, it is transformed into a single delimiter ready to commute.

-

Delimiter extrusion. If a delimiter points to the output port of some operator, it appears profitable to extrude it to the operands, causing its residuals to interact with other nodes earlier in the reduction. Keeping the delimiter inactive until the operator returnes a value results in much lower performance, because we want delimiters to disappear as early as possible.

-

References. A reference is a special node that represents a C function taking zero parameters & returning a lambda term. When the value of a reference is needed, the function is called, & the obteyned term is expanded to a corresponding net in a single interaction. Instead of adopting references, we could have a fixed-point operator as in YALE 8, but references tend to be farre more efficient in practice, inasmuch as they avoid having the overhead of continuouse duplication. In addition to improved efficiency, references support mutual recursion in a natural way, essentially acting as global function definitions.

-

Translation through bytecode. With references, it is now crucial to be able to build nets efficiently, for this happens each time a reference is forced to expand. We therefore adopt translation through bytecode: when a reference is about to expand, we translate its expansion to a compact bytecode representation that describes how to build a net corresponding to the lambda term; then we execute this bytecode & store it in a special cache for future usages. This scheme allows us to avoid repeatedly traversing the same lambda term, which will enable us to carry out term-level optimizations without loss of performance.

-

Graphviz intergration. Debugging interaction nets is a particularly painfull exercise. Isolated interactions make very little sense, yet, the cumulative effect is somehow analogouse to conventional reduction. To simplifie the challenge a bit, we have integrated Graphviz (in debug mode onely) to display the whole graph between consecutive interaction steps, if requested at compile-time in

optiscope.h. Alongside each node, our visualization also displays an ASCII table of port addresses, which has proven to be extremely helpfull in debugging variouse memory management issues in the past. (Previousely, in addition to visualizing the graph itself, we had an option to display blue-coloured "clusters" of nodes that originated from the same interaction; however, it was viable onely for sufficiently small graphs, & onely as long as computation did not goe too farre.)

- Despite that interaction nets allow for a huge amount of parallelisme, Optiscope is an unpretentiousely sequential reducer. We doe not plan to make it parallel, because it is unclear how to preserve Lévy-optimality in this case.

- We doe not guarantee what will happen with ill-formed terms, such as when an if-then-else expression receives a lambda as a condition. In such cases, Optiscope's behaviour is considered undefined.

- Optiscope cannot detect when two syntactically identical configurations occur at run-time; that is, the avoidance of redex duplication is relative to the initial term, not to the computational pattern exhibited by the term.

- On conventional problems, Optiscope is in fact many times slower than traditional implementations, wherefore it is more of an interesting experiment rather than a production-ready technology.

Thanks to Marvin Borner, Marc Thatcher, & Vincent van Oostrom for interesting discussions about optimality & side effectfull computation.

Footnotes

-

van Oostrom, Vincent, Kees-Jan van de Looij, and Marijn Zwitserlood. "Lambdascope: another optimal implementation of the lambda-calculus." Workshop on Algebra and Logic on Programming Systems (ALPS). 2004. ↩

-

Pinto, Jorge Sousa. "Weak reduction and garbage collection in interaction nets." Electronic Notes in Theoretical Computer Science 86.4 (2003): 625-640. ↩

-

Lamping, John. "An algorithm for optimal lambda calculus reduction." Proceedings of the 17th ACM SIGPLAN-SIGACT symposium on Principles of programming languages. 1989. ↩ ↩2

-

Asperti, Andrea, and Stefano Guerrini. The optimal implementation of functional programming languages. Vol. 45. Cambridge University Press, 1998. ↩ ↩2

-

Jones, Simon L. Peyton. "Implementing lazy functional languages on stock hardware: the Spineless Tagless G-machine Version 2.5." (1993). ↩

-

Jonsson, Peter A., and Johan Nordlander. "Taming code explosion in supercompilation." Proceedings of the 20th ACM SIGPLAN workshop on Partial evaluation and program manipulation. 2011. ↩

-

Asperti, Andrea, Cecilia Giovannetti, and Andrea Naletto. "The Bologna optimal higher-order machine." Journal of Functional Programming 6.6 (1996): 763-810. ↩ ↩2

-

Mackie, Ian. "YALE: Yet another lambda evaluator based on interaction nets." Proceedings of the third ACM SIGPLAN international conference on Functional programming. 1998. ↩